On January 28, Tarek said to his wife:

“I want to participate in the demonstrations.”

Rania (his wife) looked at him, taken aback.

Tarek said, “Don’t worry, one cannot run from his destiny”

With the passing of time, the warden softened and allowed inmates to socialize, eat and pray together. They even cooked in the courtyard after creating a sort of outdoor kitchen. They built an oven, which accommodated baking for some three hundred inmates. They set up a small garden in the courtyard. One prisoner attempted to escape, and was caught outside the prison but within the military barracks. This backfired on all inmates as the warden further tightened the conditions overnight after they had been relaxed. Unfortunately, after the attempted escape, the guards destroyed both the garden and the kitchen. Mohamed felt hopeless, as it seemed that conditions had returned to the unbearable starting point.

Ali will never forget the sight of a child whose eye was bleeding and he recalls a moving brief conversation with his treating doctor at the makeshift hospital.

The doctor said, “Drink this juice.”

The child replied, “How can I drink juice when children are dying?”

After humbly declining the juice and patching up his eye, the child ventured out into the square where a bullet hit him in the head, killing him. This boy refused to drink juice in solidarity with the innocent lives only to join them a short while later.

Friday morning was quiet and solemn like the calm before a storm. Rania and Tarek were talking in their bedroom.

Rania said, “Watch out, it is rumored that mobile phones are

going to be cut off today.”

Tarek said, “I don’t think so, at 7 o’clock this morning I was just

talking to my friend in America.”

Rania replied, “Just check your signal now.” He told her that he

had a full signal.

Rania told him, “Switch off your mobile and turn it on again, maybe the signal is false.”

Tarek did as she asked and said, “You are right, there is no signal.”

He showered and wore his blue jeans, black sweater, and a dark blue jacket. Before the Friday prayers, he hugged, kissed and said goodbye to his wife and daughters as any other Friday and left, heading to the mosque and afterwards the demonstrations.

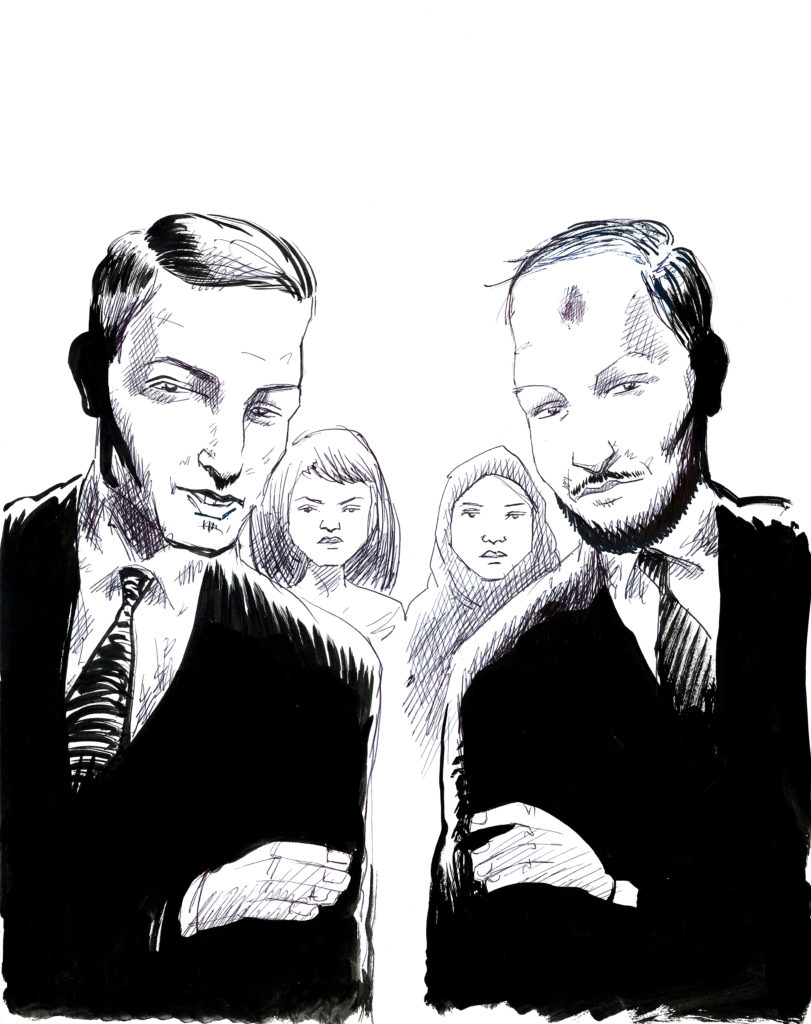

As Lina got furious with this growing resentment and disrespect, she joined the supporters of the ancien regime. With the insecurity looming over the country, it was not easy convincing her family to join a demonstration. She had to argue with her husband to get his permission for her to leave and of course, her mother was wholeheartedly against it as she supported the revolution.

Lina said, “I have to be proactive and go to the street to show

support to Mubarak.”

Her mother replied, “You must be out of your mind. Did you

not see the men and women who have been wounded or

killed?”

Her husband said, “Lina, it is not a good idea. The situation is

dangerous.”

Lina replied, “Well I have to go protest and get my point of

view heard. Not all of Egypt wants President Mubarak to step

down right away. We need to go to show our support that he

should finish his term.”

Her mother said, “I am not comfortable with this at all,” her

eyes swelling with tears scared for their safety.

Her husband said, “Well we need to go in a group.”

Readers Reviews

I enjoyed reading it immensely. The authenticity in shedding a different light on those fateful 18 days in the history on Egypt and seeing those days from different and sometimes opposing perspectives is by all means an eye opener. The objectivity of the writer is commendable since, as an Egyptian young woman, she must have had her own opinion, experience and stance with respect to the events. It is impressive that this didn’t interfere in her account of the 18 personalities in such a polarized society at the time. Very recommended to read. I am re-reading it as I am writing this review.

I use this book to teach my undergraduate course on power and culture. The author beautifully brings together various perspectives and stories in a way that captures the complexities of the Egyptian Revolution(s). The genuine and authentic nature of these stories really brings out the contested nature of the revolution and leaves one with a sense that these issues are ongoing. The author did a great job of editorializing these various stories and telling them in an authentic, yet concise way. The author’s passion is also a powerful addition to the narrative. This book and its analysis have stood the test of time and continue to be relevant in understanding today’s Egypt and the world.

“Nadine is a very authentic story teller … amplifying the voices of society with its

diverse and complex makeup while focusing on the human side of what happened

during the 18 days in Tahrir during the revolution! It’s a smooth enjoyable insightful

and moving read that sheds light on various perspectives through a neutral inclusive

narrative.”

“Nadine illustrates the stories with authenticity and compassion. They are diverse but

all part of the society, Nadine made a big effort to bring them to light. Her language

is both simple and rich.”

Shaimaa recalls it clearly, as if it were yesterday. She was at a friend’s party in Rehab compound, one of the suburbs of Cairo, when she heard that the President has stepped down. She cried while everyone around her was jumping and dancing with jubilation; sorrow amidst celebrations. Her friends, mostly single men and women, well-educated elite dressed in tasteful clothes, who like to party and enjoy nightlife and are frequent voyagers abroad, were celebrating as they never have before. The joy transcended their high school prom party, graduation

party, managerial or director promotion and even their wedding celebrations. The loud music muffled her ears; in stark contrast with her friends, she felt as if locked in a dungeon with no windows and everything was pitch-black. Shaimaa felt a heavy weight burdening her heart and sadly foresaw the looming anarchy, which the nation has been

witnessing since the revolution.

Almost all the police stations were under attack; it was like a domino effect, one fell after the other within an hour. The first station attacked was Masr El Adeema. These stations are normally loaded with weapons in addition to detainees, imprisoned for a short period awaiting prosecution. At the time, Captain Mo believed an organized group must have orchestrated it but he was not certain. However, today he

knows that Ikhwan were the mastermind behind this attack. He has heard that trained mercenaries from abroad lent them a hand. Demonstrating is one form of activism; but attacking a public institute like the police station is not activism. It is nothing but unlawful aggression. To attack the police stations was an act of treason. Some of the assailants were armed and charged with hatred.

Shortly after that, Sayed arrived home and slowly climbed up the stairway to his apartment on the fifthfloor. His wife was shocked to see her husband came in, with dirty and bloody clothes and with blood on

his forehead.

Scared Um Basma asked, “What happened?”

Sayed lied and said, “Nothing, I got hit by a rock.”

He lied, as he did not want his family to worry. Sayed showered, skipped his dinner and lay down on his bed, unable to sleep from the blinding pain. He was really exhausted after three active nights at Tahrir

and tried to rest. His wife and daughters were silenced by shock at the sight of his blood. That first night,Sayed was pondering how he would get money for the household with his wound and inability to work.

He imagined he would return to work after a fortnight or less.

After the third and final speech of Mubarak, things appeared to be over. The game

was over. The former President handed the trophy to the army who honored him

in the first place. This move did not invalidate the revolution’s reality. It was not

a radical young officer’s military coup but rather, a handing over of power, or, a

returning of power to its source. Gehad compares it to someone who, entrusted with

a treasure and if he needs to leave it, he will return the treasure to whoever entrusted

him with it in the first place. In his opinion, it only made sense that Mubarak

returned the Egyptian treasure to the army.

Nonetheless, not all things are mutually exclusive; labeling it as either a revolution

or a coup d’etat are not the only options. Matters are not unitary; either black or

white, there is grey as well. This was the predicament. Gehad had predicted that

Mubarak would hand over his reigns to the army institution, and his prophesy had

materialized. Gehad supports a civilian revolution. The Egyptian revolution, in his

view, was neither a political nor a social revolution. The main objectives were to

increase personal freedom and equal rights, which define a civic revolution in general.

Gehad has been advocating these rights with his support of liberalism while he was

working at the NDP, but with no avail.

Multiple things happened simultaneously in Egypt in 2011. A civil revolution-cum-

coup took place; it was a special type of coup, not a radical or Latin American type

coup, In addition to widespread social disturbance in the form of demonstrations and

strikes demanding better pay, there was, not in the least, the powerful silent majority.

All these variables were in motion, at some times intersecting and other times not.

Hanan was personally shocked, and cried rivers over the inexplicable injustice she

met. Dr. Beshr and Eng Omar Abdallah, who worked at the Supreme Guide’s

office, called Hanan, requesting a report on the sit-in. Impressed by her report, as

she mentioned the behavior of the brothers, and stated what Ikhwan needed to do to

change and reach their ideal.

Omar Abdallah said, “Hanan, are you not a sister? Don’t you attend sessions?”

Hanan replied, “I attend.”

Omar said, “While writing the names, a sister said that you are not a sister. As you

want to run in the Syndicate elections and removed your name from nomination

list of Ikhwan.”

Hanan, upset, went to talk to the election specialist.

She asked him, “Why is my name not on the nomination list?”

The electoral specialist replied, “I told them to add your name under the coalition list.”

Ironically, she ran for the elections as non-Ikhwan, and her list won. She works

with Ikhwan at the Syndicate, but does not attend their organizational meetings.

She stopped being as personally involved as before. Hanan was unceremoniously

disbanded from Ikhwan after her twenty years of voluntary service.

Now being an outsider, she finds the words used by Ikhwan strange, like ‘halaka’

and ‘osra’, (circle and family). They are all exclusive. Feeling immense depression,

Hanan decided to take up music. She is taking violin lessons at the Music Faculty at

Zamalek, where we met the first time.

MTV interview

In this televised interview Nadine shares her story behind the making of her debut book Tahrir Voices: 18 Ordinary Egyptians in 18 Extraordinary Days.